It seems the older I get the rarer it is that I'm really grabbed by a book. Oh, sure, I find books I admire, books I like, even books I love. But one that grabs me, that sticks with me when I'm driving, walking, working, even sleeping....those are rare books indeed. Steve Erickson gifted me with one with his novel Zeroville.

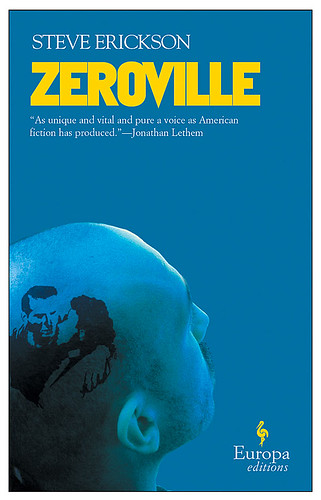

Although the concepts in the book are kind of a Pynchon meets Delillo ingested and spewed out via a transliterated chat with Luis Bunuel, the plot is actually pretty straightforward. It's the late 60's and a man named Vikar is booted out of the Architecture program at Mather Divinity College----he made the confounding error of designing a church without a door for his final project. Vikar responds to this letdown by following the lure of his other love---film--by getting a picture of Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift in From Here to Eternity tattooed on the side of his shaved head and hopping a bus to Hollywood.

The early sections of the book transform into a guided tour of Hollywood through the eyes of a man who has ingested nearly every bit of film trivia possible. Vikar moves into the Roosevelt hotel---which may or may not be haunted by D.W. Griffith--- and can't help but tell everyone around him everything he knows about the history of film. His architecture background serves him well when he's hired as a set designer at a studio. He gradually works his way up to the role of film editor meeting an odd cast of characters as he learns, lives and breathes the world of film.

His career takes some odd turns. Sent to Spain on one job, Vikar's kidnapped by a revolutionary faction that wants to use his talents to create propaganda films to help their cause. Later, he becomes the first film editor to win an award from the Cannes Festival all because no one really understands what he's trying to do. When the late 70's hits like a tire iron across the face Vikar develops a near-violent obsession with punk rock.

Vikar will likely drive some readers batty. He's knocked around by circumstances, rarely making choices or decisions of his own except at a couple of key moments. He's also inexplicably odd. A more traditional author would spend time getting us more firmly into his life and history so we can understand or even feel his mental state. Despite its readability this book is anything but traditional. Erickson more often than not uses Vikar not so much as a character but as an easel to lean his satire, jokes and theories on.

Erickson's writing is highly referential. Classic films and actors fill every section, but he also tosses out bits about cult films, art films, the lives of studio execs and industry business. But the references often blur the lines between real film history and fabrication. One character who continually pops up throughout the novel is a mildly revolutionary script writer/director we know only as Viking. But through various clues dropped throughout the book----that he co-wrote Apocalypse Now and worked on the Conan movies---you can figure out that Viking is probably based pretty solidly on John Milius. Soledad, a sexy actress who never quite makes it, seems to answer the question of what would have happened to Soledad Miranda if she hadn't died at such a young age. Other characters like Dotty Langer, who seems more real than anyone in this hyper-real book, seem to be completely born out of Erickson's imagination.

Criticism and meta-art also play a large role. Several characters---Vikar included---launch into page-long diatribes on the role of film that are both funny and fascinating. Vikar, for example, believes a film and its true meaning exist beyond the constraints of sequential time and we only structure movies that way to make the meaning more easily interpreted. Erickson slyly uses this idea for structuring his own novel by referencing moments that occur at the end of the book as early as page 50.

All of this, of course, is wonderfully funny---and fun---if you have a love of film and film history. For readers who don't it can become a bit like watching a Simpson's episode where you just don't know any of the cultural references. You think the jokes might be funny or even profound, but you really aren't sure because you have no real idea what the jokes are about.

Excelsior

No comments:

Post a Comment