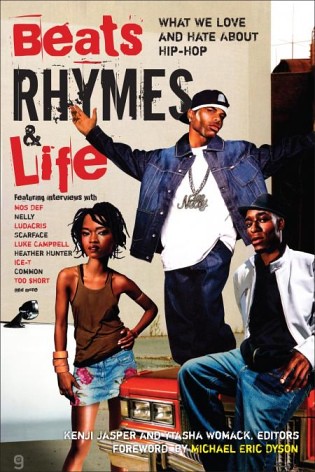

After more than 30 years of pumping out rhythms and rhymes, there’s no arguing that Hip Hop has made a huge impact on popular culture. And much like Jazz and Rock before it, Hip Hop is now moving through the growing pains of just being a popular form of music to becoming a genuine art form with a respected place in cultural history. Editors Kenji Jasper and Ytasha Womack have done an excellent job with their book Beats, Rhymes and Life in collecting a variety of essays and opinions exploring and deconstructing the music, lyrics and imagery of the music videos surrounding Hip Hop and Hip Hop culture as they try to answer the question of its place in the world.

Several of the essays examine the image of Hip Hop and its obsession with bling, violence towards women and glorification of drugs; are the artists providing social commentary by portraying the worst of inner city life or are they adding to the problems by glorifying it? Other essays, like the forward by critic and academic professor Michael Eric Dyson, remind readers of Hip Hop’s early connections with the civil rights movement but express some regrets over its more recent developments. In fact, if there's one general thrust to most of the content of the book it probably follows Dyson's opinion that Hip Hop, by and large, was about personal artistic expression and serious commentary. The title of the book, after all, comes from an album by Tribe Called Quest, one of the more socially active Hip Hop groups around. But there's a general feeling that Hip Hop's left this behind for the glitz, bling and bank rolls it now generates by way of Mtv.

Along with the essays, the volume also includes a number of pointed interviews with well-known Hip Hop performers like Ludacris and Too $hort as well as Rob Marriot, co-founder of the Hip Hop culture magazine XXL. The interviewers are obviously well informed fans but don’t shy away from asking difficult questions. Too $hort’s interview is particularly interesting as he expresses his opinions of trends in the industry. "My personal theory” he said in the interview “is that rappers don't really lose it lyrically, they just don't pay attention to the production. That first album, when you was broke, came out the bomb, but then [with] that next one you've got some jewelry. You got a car. The girl wants you. And then you go into the studio and you got the ego and the ego can't make records. Records gotta come from within."

Despite the contributions coming from a number of academics and high-minded cultural critics, Jasper and Womack make this book accessible by keeping the hyper-critical jargon to a minimum. Readers should be aware that this is not a history of the music like Jeff Chang’s Can’t Stop Won’t Stop (Picador, 2005), but a collection of writings that assumes readers at least know the big names and events of hip hop. My own knowledge of Hip Hop is pretty limited. I know a good bit about the early days because of its connections with electronic and improvisational music. And I know the early to mid-90’s stuff, because that’s when I was in college and Hip Hop was the party soundtrack every where you went. So while I felt lost at time with the references to names of performers and albums I’ve never heard of, I still got the gist of what the writers and editors wanted to get across.

Smart fans of the art form, though, will get the most out of this. They will find a thoughtful, balanced book that gives them the opportunity to think about the medium and make their own decisions about Hip Hop’s place in history.

Excelsior

No comments:

Post a Comment