Love him or hate him, through the Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy Tolkien created a template for modern fantasy. Even more than forty years later nearly every fantasy novel written since Tolkien’s days is either patterned after or a reaction against the standards Tolkien set. Just when fantasy was starting to slip away with authors like Jeff Vandermeer and China Mieville really branching out to new territory, the movies came out and breathed new life into Tolkien’s slowly waning influence.

One of the reasons The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings work so well is that Tolkien developed a fabulously intricate back story detailing the rich history of his fictional world known as Middle Earth. While much of this material was published posthumously in books like The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales, Tolkien delivered it in a loosely connected way that makes it pretty tough to read. While millions have read his novels, few but even the most dedicated of fans have dared slog through the entirety of the pre-Hobbit material.

Edited by Tolkien’s son Christopher, a new volume titled Children of Hurín draws from both of these earlier sources to pull together a complete single narrative set in pre-Hobbit Middle Earth. Turín, son of the human lord Hurín and the Elven lady Morwen, becomes a pivotal force in the ongoing battle against evil in an epic adventure full of action, intrigue and clever battle scenes. The early parts of the story focus on Turín’s young life; Morgoth, master of a young dark lord named Sauron, captures Turín’s father forcing Turín to spend his formative years living in the safety of the Elven kingdom. When he reaches manhood Turín is wrongly judged for the death of an elf and banished for the rest of his life. After some anecdotal adventures he manages to become the leader of a ragtag band of forest outlaws that cause no end of problems for the Orcs, dragons and other powerful forces of evil trying to usurp the kingdom. Plotwise, its all pretty exciting in a massive chivalrous quest kind of way.

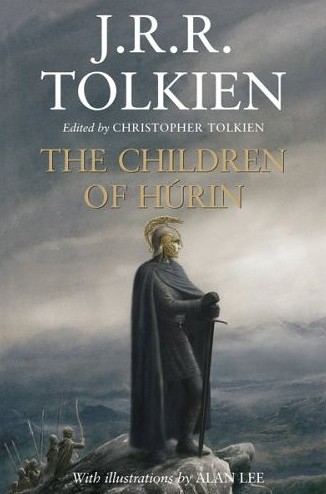

Alan Lee’s illustrations, though, are pretty incredible. Both black and white drawings and full color paintings, they come solidly from the traditions of fantasy illustration and bring dramatic visuals throughout the book.

For me probably the greatest innovation Tolkien made with his novels was the creation of the Hobbit itself. Up to Tolkien, fantasy literature was still based squarely in the ideal of retelling the age of chivalry and tales of daring-do. The Hobbits end this by introducing characters that aren’t interested in things like glory and power. Both Bilbo and Frodo work as central characters so well because they are essentially modern characters living in a fantasy world. As a character Turin is charismatic, brave, cocky and as equally skilled in getting into trouble as he is in getting out of it. But he is all old world. His motivations, relegated to basic things like revenge, are simple and lack the depth we expect from central characters today. I don’t think this was Tolkien being lazy or lacking skill so much as him trying to emulate an older style. But still, I think a lot of people will have trouble relating to Turin as he bounds from adventure to adventure.

A secondary barrier is the language. Tolkien seems to draw a lot from the King James version of the Bible in what rhythms and sounds he chooses. While this works wonderfully in descriptions, particularly of landscapes, it falls apart for me with the dialogue. You get crazy stuff like this:

“I did not come with the thought of battle,” said Turin, “though your words have waked the thought in me now, Labadal. I must wait. I came seeking the Lady Morwen and Nienor. What can you tell me, and swiftly?” (185)

Yes, you do get dialog like this in the novels. But it primarily came from royalty and was modified by characters like the Hobbits that speak in a manner closer to our own. It’s the only style of speech here and it gets a little overbearing. At least it did for me.

The language and lack of depth in characterization might intimidate casual readers but more ambitious fans of fantasy will find a massive and wide-spanning plot that reminds us why we continue to place Tolkien on the zenith of fantasy literature after so many years.

Author and critic David Louis Edelman has a write-up that digs more deeply into the Middle Earth history of this book than I can. He's also been blogging about a number of other Tolkien works, so look through his blog for related entries.

Excelsior